Here's an example of Gestalt dream technique in action, using one of my own dreams, from a period when I was experiencing uncertainty about my next steps in my professional and creative life. I start by recounting the dream (no dream is too short—even a fragment can yield rich results). I describe the overall mood or atmosphere, then inhabit each significant part, animate and inanimate.

Dream: I’m driving into a city with my mother and some kids. I see dark, ominous clouds of various shapes and levels amassing right over the city. As we drive over a bridge into the city, I see a black cloud in the shape of a boot drop down. It seems to hit the head of a swimmer. This action has a sense of gangster warfare—the old-fashioned Italian type—menacing. But there’s also a sense that these gangsters carrying out this aggressive battle are not interested in us ordinary folk.

Mood: Ominous but intriguing, like a quickly evolving film that turns cartoon-ish. In making this shift it becomes almost funny in an edgy, hysterical way while at the same time becoming even more concretely menacing—a boot falling from the sky and kicking someone in the head appears as a surreal cartoon but is at the same time more substantive than clouds massing and swirling.

“I”: I wonder if we’re insane for barreling along right into the storm. I wonder if we should be pulling off to the side. I know I’m the only alert adult present—I can’t count on my mother to make decisions in this situation. I wish to be passive but I feel I should be active. But I don’t know what to do, and I feel pulled forward by the momentum of the car, of the unfolding scene.

Mom: I feel placid. I hate driving. I’m so glad my daughter is driving so I don’t have to take responsibility. I can just be, gaze, observe, think my thoughts. My daughter can handle everything.

Kids: The grownups are acting like it’s OK to be in this situation. So we guess reality is supposed to be this frightening. It’s also exciting, watching ourselves roll right into this vision. It’s like a film or even a cartoon. It’s real and unreal, troubling and wildly entertaining. We’re just drinking it all in, no filters.

Clouds: We are angry and nothing can stop us. We move through the air like we own it. Out of ourselves we form a menace people might laugh at. But watch us form into a huge hard boot that kicks a swimmer hard in the head. Now we are this boot. We form from air but we become hard mass, a weapon. Call us cartoon, but you wouldn’t want to be that swimmer. We will dominate this war with the other dark powers.

Swimmer: I was just swimming and got totally socked with pain. This is what I get for letting down my guard. I have enemies who want to destroy me—I can’t relax ever.

Bridge: I provide access to the densely populated, magical, energetic city. I can’t keep people in or out but if they decide to come, I’ll be their passageway. Once you’re on me you can’t get off because I’m over water.

Water: In me, both pleasure and danger can happen. Beings can swim skillfully through me or drown. I separate the city from the rest of the world. In that way I’m like a moat, something that must be crossed over in order to enter the action, the center.

City: I’m where the action is. I’m what humans have created. I’m all artifice but at the same time I’m where the great human party happens. I’m the place of the least and the most contact. I hold promises that I deliver and foil. In a storm, like now, it’s dangerous to be in me with my tall buildings that could be hit and fall, crushing denizens.

If I were to continue working with this dream I would take one or more of the parts that seem most "not-me" and demonstrate their energy physically. For example, I might become the clouds massing in the sky, and the boot falling and hitting the swimmer. I might then "speak" those parts as "me, Sarah" to help integrate them into my conscious psyche.

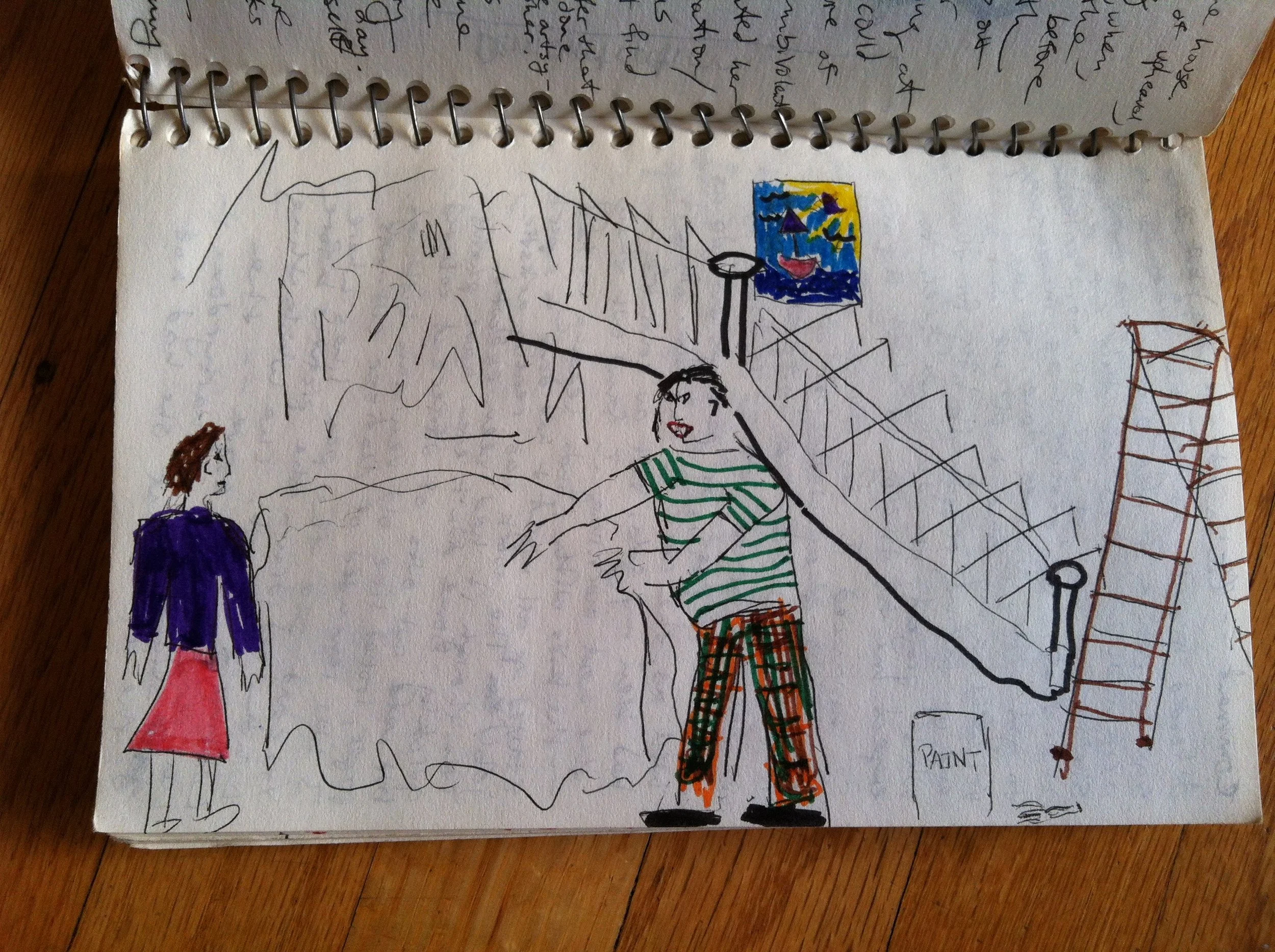

I could go even further, representing the dream or an aspect of it in an artistic medium (skills not necessary!). Or I might prefer to move on to analyzing another dream. Either way will yield insights.

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016