Jo as a toddler with her parents and older brother.

By creatively expanding the concept of the family unit to include the larger world, Joann Wong fueled a lifelong passion for public service. This is the second in a five-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with her. In Part 1, Joann described her parents’ traumatic beginnings, immigration to the States, and resilient adaptation strategies.

S: You went to Stanford as an undergrad. What did you major in?

J: I started out pre-med but realized at some point that I wanted to explore other options in health care. I ended up majoring in Human Biology with a concentration in Child and Adolescent Development.

S: What had initially drawn you to medicine?

1977—Jo (far right) with her brother, cousins, and maternal grandmother.

J: When I was ten, my mom’s brother got a rare form of cancer. I was really close with his kids—we spent summers together. We watched my uncle deteriorate and die. My mom played a big role in caring for my uncle and she was really important to my cousins, because our families spent a great deal of time together. Being so close to someone with terminal illness impacted me. Also my dad really loved kids, and that rubbed off on me. When I went to college, I thought I’d be a pediatric oncologist. I volunteered at a camp for kids living with cancer. I loved the kids but the fact that they were so sick was hard on me. And academically, while I was inspired by science, I didn’t excel at it. I didn’t do well in the famous freshman weed-out course, Chem 31.

I thought, That’s fine, if I don’t become a doctor, I could…. I couldn’t finish the sentence. That scared me more than giving up my plans of going into medicine. A doctor I had been shadowing said, what matters most is following your passion. So I asked myself, What sparks passion and excitement in me? I knew I wanted to stay in health care but I realized I was more called to the service side.

14-year-old Jo and her family.

1987—Jo with her maternal grandmother, parents, and brother.

S: That ties back to what you alluded to earlier, that your family’s emphasis on supporting the family somehow translated in your mind to supporting others far beyond the family unit.

J: Yes. I was also very inspired by the example of my piano teacher. She had a strong Christian faith. She was patient, loving, and devoted to helping others. Interestingly, I was surrounded by Christianity as a child—the uncle who died was a pastor—but my parents kept Christianity at bay. My mother felt that the gossip at church didn’t model Christian values. And my dad thought all Christians were crooks because he knew there were these wealthy televangelists cheating people out of their money. As an adult, though, I identify as a Christian.

S: When you first graduated you worked on HIV issues, is that right? What led you to that arena?

J: I was a product of ’70s and ’80s, and the HIV epidemic was a fact of life. I was drawn to the social justice aspect of the disease as well as the compassion I felt for people being discriminated against because of their illness. I’d learned from my parents to stick up for my principles, fight against discrimination. Once when I was 12, my mom and I were in a parking lot and some white guy shouted at her, Why don’t you go back to your own country?

With other undergrads, Halloween 1988.

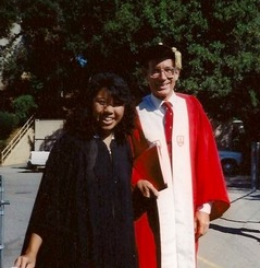

Graduation Day, with Stanford President Donald Kennedy.

My mom said, Why don’t you go back to your own country because the only people who belong here are the Native Americans! (Actually she said “Indians.”) I thought, Here’s this supposedly docile Asian wife who cooks and cleans and drives her kids around, being such a bad-ass!

I do have to say sometimes it goes too far. Once we were coming out of Safeway and she looked at her change and realized she’d been short-changed by a nickel. She started marching back into the store. I said, Mom, it’s only a nickel, let it go. She started lecturing. “Joann Wong! This is about the principle!” I always know I’m in trouble when she uses my whole name.

S: Tell me about the work you did in HIV.

All grown up.

J: Right out of college I received a fellowship to intern at the State Department of Education in Sacramento. I worked on a program called “Healthy Kids, Healthy California,” doing a literature review of HIV curricula being taught in schools.

After that I got a job teaching HIV prevention education to middle and high school students in Santa Clara County through the Mid-Peninsula YWCA in Palo Alto. That position helped me understand women’s and diversity issues more. I had phenomenal role models there—including my boss, Kay Philips, the executive director—who were working to empower women and eliminate racism. They were strong; they spoke up.

When a development director position became open at the YWCA, I applied for it. I was up against a woman who was maybe 15 years older, but I got the job. I was given intensive training in fund development, communications, and media relations. I saw that the people who hired me were walking the talk of empowering women of color.

In that period I took a six-week trip to China with my family. I got a deeper understanding than I’d ever had of what it means to be Chinese American.

Next installment: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese!